Reformation

Note

Inspired by the life of the German Renaissance painter Lucas Cranach the Elder, Reformation was conceived as I visited an exhibition showcasing the artist’s work for the Hohenzollern electors. Most of the story had come to my mind by the time I’d finished viewing the paintings. Alongside the artist, the play features other historical grandees from the period: Elector Joachim I Nestor, his brother Archbishop Albert of Mainz, and the artist’s son, Lucas Cranach the younger. I introduced three imagined characters: a peasant girl, Ava; her bitter uncle, Benno; and the peasant matriarch, Gretel.

A historical play, then. But the events it portrays might happen (with one or two modifications) anyplace and anywhen. The play asks some questions about the relationship between art, desire, and power. Those characters not in positions of influence are offered stark choices between living in some degree of comfort or being hung out to dry. The mighty can always get what they want, materially... Some things never change.

Reformation is a play about those who don't make the history books. I wanted to tell the story of a poor young soul who finds herself adrift in this world, where the desires of the powerful hold sway and dreams can disappear.

Story

Berlin. Eva learns that the celebrity artist Cranach is visiting her city. A chance meeting in the market place leads to romance with the artist's son. Eva gets the chance to model for Cranach’s latest painting, ‘The Rape of Lucrece’.

When Joachim, the all-powerful Elector of Brandenburg, sees the sketches of Eva, he wants the model. Is Cranach willing to sell the human his son loves?

In an age where upsetting the powerful meant obscurity or death, what's a poor girl like Eva to do?

Casting requirements: 2 f, 5 m

Reformation is published by Playdead Press

Production(s)

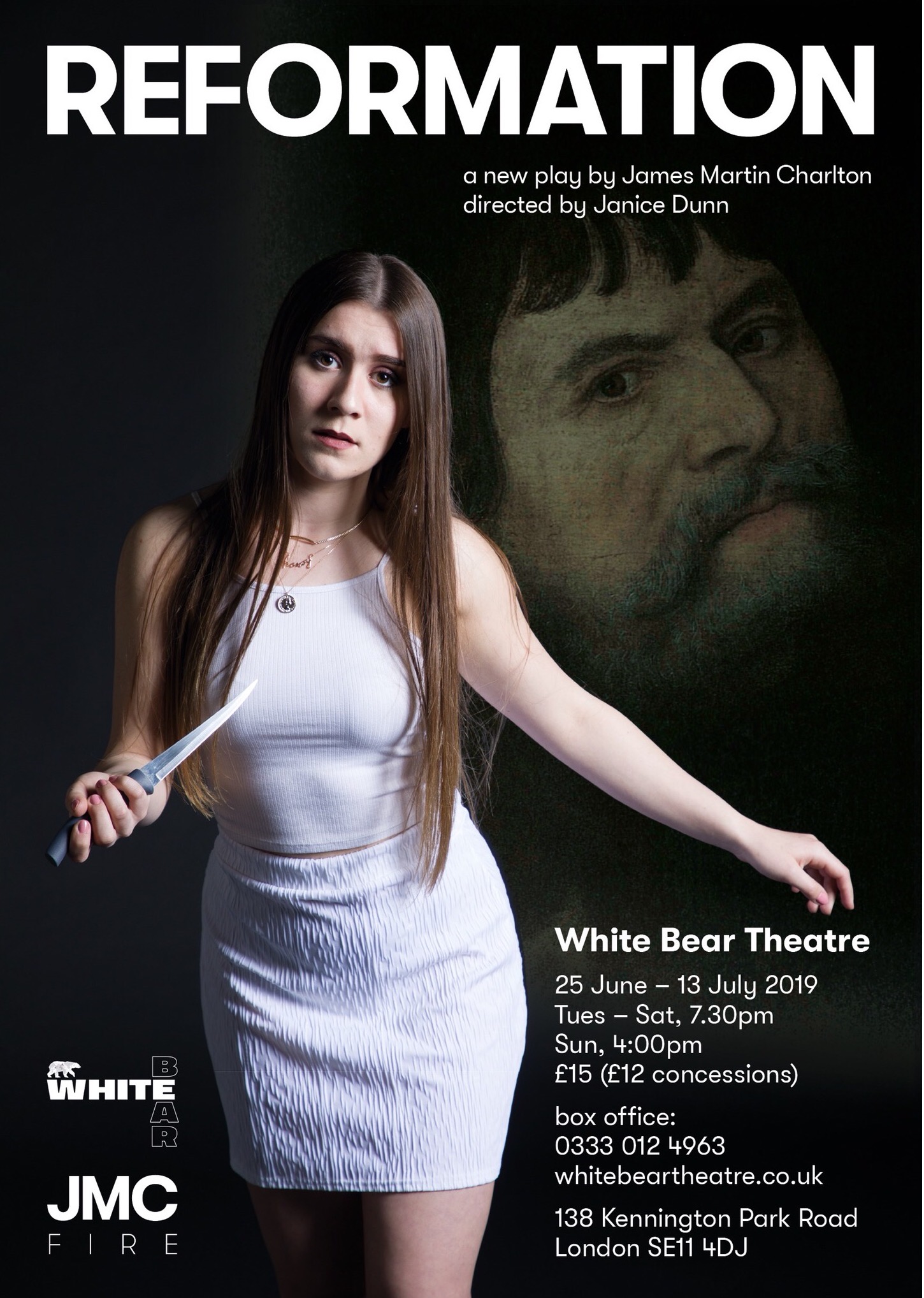

Premier: White Bear Theatre, 25 June – 13 July, 2019

Cast: Alice De-Warrenne (Ava), Ram Gupta (Lucas), Matt Kelly (Albert), Adam Sabatti (Benno), Imogen Smith (Gretel), Simeon Willis (Joachim), Jason Wing (Cranach).

Directed by Janice Dunn, designed by Lucy Bond, lighting by Anna Reddyhoff

Produced by Nayomi Roshini for JMCFire

Media

Trailer for the 2019 JMCFire production:

Seminar at Middlesex University:

Press/Audience Reaction

"Artists have always captured the imagination of writers – for novelists, playwrights and screenwriters, the idea of the tortured genius fighting for recognition or the lonely romantic struggling to express their feelings in art offers an immediate entry point to a story. Some focus on a particular period in an artist’s life, like Nicholas Wright’s Olivier Award winning Vincent In Brixton about van Gogh’s time spent living in south London. Some delve into the theory of art, like John Logan’s multi-award-winning Red about Mark Rothko. Some, like Sondheim’s Pulitzer Prize winning Sunday In Park With George about Georges Seurat (returning to London in 2020 starring Jake Gyllenhaal) take a particular painting as their starting point. In the case of Reformation by James Martin Charlton, now playing at the White Bear Theatre in Kennington, the subject is the German renaissance painter Lucas Cranach, and Charlton’s way into the story is through the experiences of one of Cranach’s models, Eva. A chance meeting in Berlin between the poor Eva and Cranach’s son leads to a relationship, to Eva being chosen as the model for the painter’s Rape of Lucrece, and ultimately to the all-powerful Elector of Brandenburg’s discovery of and desire for Eva. Both Cranach and Eva are faced with a moral question. The painter has to decide whether or not to destroy his son’s happiness for his own commercial success (in keeping with the views of the time, Cranach spends a lot of time in the play talking about the commercial value of art, far more than he does the spiritual or aesthetic value). Meanwhile, Eva has to decide how much she is prepared to sacrifice her body in exchange for financial security, and whether being “the girl in the painting” is a good thing or not. It is all too easy, with the distance of time, to celebrate the artists of the Renaissance and beyond who painted nudes, to romanticise the work and suggest that it glorifies the human form or that those artists are recalling the art of ancient Greece and that the subject matter is based on art historical study. However, Charlton’s play reminds us that any commercial exchange that involves a person’s body has consequences, and the beautiful paintings of history were almost exclusively painted by and for men. Cranach’s subject, agreed between painter and patron, is hardly selected to celebrate either art history or mythology, as the subsequent events make abundantly clear. Charlton also explores the religious moment in which these events unfold, with the ‘everything can be forgiven if you confess’ view of opulent Catholicism. Matt Ian Kelly is constantly entertaining as the Archbishop of Mainz, attempting to balance the credibility of confession with his own unholy desires, while Alice De-Warrenne convinces in the role of Eva, the strong-minded young woman who fights against her family to secure independence but who must then decide what to do with that independence – if, in fact, she can ever be truly independent of the powerful figures around her. The play is written in a resolutely contemporary vocabulary and presented in modern dress, to mixed success. The modern text has an energy that is sometimes lost in translation, and the modern dress could be far bolder – the anachronistic approach is designed to present the story in the context of the #metoo movement, with the Elector clearly a Weinstein-style character, but the costuming is too general for that to be entirely successful and there could be a greater commitment to playing with the anachronism of the text. Nevertheless, this is a strong reminder that neither the passage of time nor the context of art should ever lull us into disregarding the kind of abuses that the powerful can wield.” - James Hadrell, South London Press

“James Charlton has written a dense and layered work with much texture to experience but perhaps just a tad too much to grab in the White Bear’s small and immediate theatrical setting. His play is interesting and well-constructed but, in its current staging, succeeds even more as a dramatic study (with teleplay potential) rather than as the fundamentally gripping theatrical drama its central conflict promises in the synopsis. An ambitious piece of ‘speculative fiction’, Charlton imagines figureheads of the Protestant Reformation encountering one another and serving as an allegory for the wider social forces that prompted it and continue to result from it; with the political very much the personal then as now. Unlike John Osborne’s 1964 Tony-award-winning play Luther, we are not treated to a historical epic spanning 25 years of religious revolution. Rather, Charlton’s work takes place over a matter of weeks in a ‘kind of 1529’: twelve years since the dramatic nailing of 95 Theses to Wittenberg Cathedral’s door that legend (and a few historians) tell us kicked off the Protestant Reformation. Initially, I was unconvinced about director Janice Dunn’s choice to stage the play using modern dress and contemporary props. But Charlton and Dunn are strong world-builders and we quickly understand we are not in the present day. The toned-down symbolism of two eras works rather well. Thankfully, their modern dress staging isn’t laboured to draw a clunky and obvious parallel to the current era but serves to place us in a dreamily familiar place that isn’t over-literal but plenty familiar. With a bigger production budget and venue, I’d be interested to see if the lighting and set design might take this non-temporal feeling further to more visceral places. Reformation is ambitious but not ‘high concept’. It imagines meetings and conversations between people whose names are iconic but whose actions need not be scrutinised for historical purposes. This production is not about hanging on every word, but rather getting the gist. Unfortunately, because there are so many words to hang on, there are moments when the audience’s cognition is over-stimulated at the expense of emotional sensation. The story is well-crafted and arrives at a skilfully-rendered crisis at the end of the first act... The second act moves at a more pleasing clip. Occasionally owing more to Westeros than Wittenberg, Charlton gives his indulgence-selling Catholics, brothers Albert and Joachim (played with great skill by Matt Ian Kelly and Simeon Willis) chewy amounts of debauchery and corruption. Careful not to take sides in the Reformation itself, his Protestant artist, Lucas Cranach the Elder (Jason Wing giving a strong portrayal), depends on their patronage (we learn he is financially over-extended for good measure) is not above moral compromise even at the expense of his own son’s happiness. Perhaps Charlton was worried about objectifying peasant-cum-model Ava in the telling as much as the story so he was overly careful to depict her humanity and build her family backstory. This would make a wonderful television drama over several episodes... Alice De-Warrenne has a big job to do as Ava and some brave performance moments. She lands some very tough moments with grace and skill. It is a pleasant subversion of the victim trope that we discover, despite all the corruption and soul-selling (with more than one direct reference to Faust), Ava is neither Madonna nor Whore – in a world where she will be commodified, she will at least seek the best price and make most of it. The gruesome inclusion of incest amongst her trajectory felt like it was also taking us to the thrills of Game of Thrones but perhaps served to remind us of the brutish and short lives of most people in ‘some kind of 1529’. Besotted and romantic lover, Lucas Cranach the Younger (Ram Gupta) is perhaps the most televisual role of the piece. He serves to create conflict and provide contrast to the dehumanised but ultra-politicised world framed by the Elector and Bishop. Gupta has a pleasing stage presence and offered some strong moments... Imogen Smith as Gretel was outstanding and should this work find its way to a longer format, I’d like to see Gretel’s backstory expanded with Imogen in it. However, for the sake of dramatic economy, the role itself might not justifiably expand... This play does not shrink from a challenge: objectification; dehumanisation; art; ideology; idolatry abuse of power; deification and demonisation of women; the rise of capitalism and the Protestant work ethic – throw a dart at 95 doctoral theses pinned to a door and you’ll hit at least one meaty theme Charlton explores. Given the scale of his ambition, he does well to tell a story at all! Although I think some of the scenes for characterisation in the domestic sphere would work well on television, they could be cut down for a tighter, tauter play. Nonetheless, Reformation is a success: it is interesting, thought-provoking and enjoyable. I can’t wait to see where it might go next!” - Mary Beer, LondonTheatre1

"Reformation is an intriguing and often amusing play by James Martin Charlton... The exploration of class and male power runs through this work and is nicely judged... I’d recommend Reformation as an interesting exploration of power with strong central performances, and some laugh-out-loud moments." - onion.london

"Schiller's grand clashes of ideas and historical moments meet the sharp, dark wit of Middleton. The play is admirably crafted, always forward moving. Imaginative re-working of the period material is well served through punchy dialogue. The evening certainly had me wondering what, if anything, we ever mean by "reformation", and from what into what. I hope that's how I was meant to respond." - Professor Eric Heinze, Queen Mary University

"Dark humour and the darker themes of religious tyranny, corruption, sexual abuse and seduction were skilfully brought to modern awareness through the contemporary language and the costumes." (...) "I liked the play which had a clever plot. This was whether the protestant renaissance painter, Cranach, would sell the woman who his son loved to the catholic Elector of Brandenburg, if the price was right. At the time Cranach’s emerging protestant church thought itself morally better than the catholic church which it considered corrupt. However trade still continued between the two communities and some will see similarities with the Brexit situation." (..) "Great Play, well written and acted." (...) “A provocative play by the skilful James Martin Charlton in the welcoming White Bear Theatre Club, you know you're in safe hands for a stimulating evening. Seven strong actors with parts to match... Anachronisms bring the world of German Art and Protestantism... We're reminded that everything's for buying and selling including human flesh... a 5-star piece of theatre."

- Audience Club members